Dr. B the Heart Doc On The New High Blood Pressure Guidelines

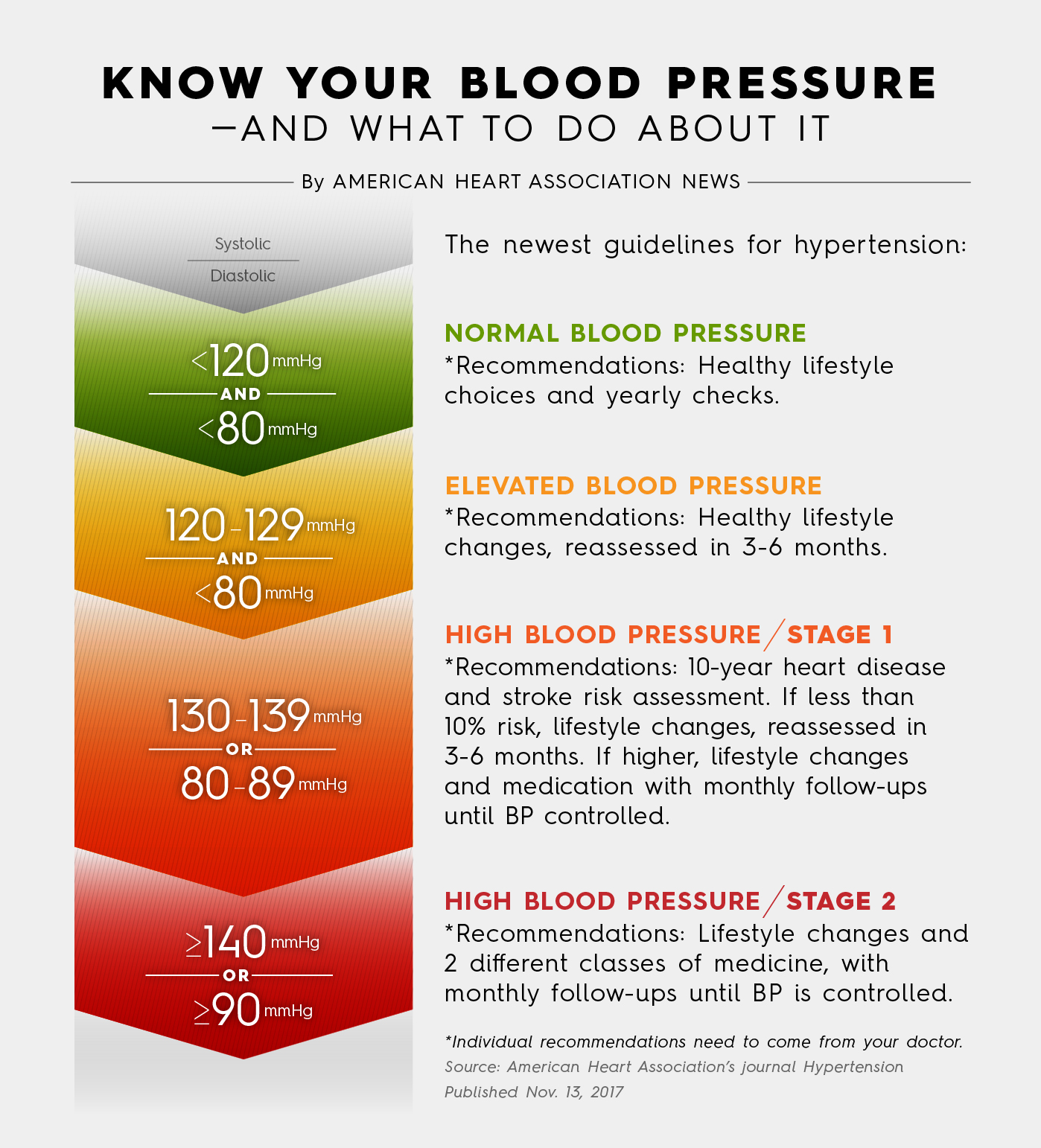

If you haven’t heard about it yet, this is big news. The American Heart Association, in coordination with the American College of Cardiology (ACC) has just changed a major guideline for how hypertension (high blood pressure) is defined in the United States for the first time since 2003. Now, if your systolic blood pressure (the first number in your blood pressure, the one “above the line”) is between 130 and 139 millimeters of mercury, or your diastolic blood pressure (the second number in your blood pressure, the one “below the line”) measures between 80 and 89 millimeters of mercury, you will officially have Stage 1 Hypertension. Before this change, we would not consider you to be Stage 1 Hypertensive until you had a blood pressure (BP) of 140/90 or above. Whereas my patients with BPs in the 120/70-130/80 range were “normal” before, now, under the new guideline, they are deemed to have “Elevated Blood Pressure” or “pre-hypertension.” The impact of this revision means that over 46% of the country will need to be treated for high blood pressure, an increase of 14%.

After reviewing the 481-page guideline, which covered various recommendations about the diagnosis and treatment of high blood pressure, here is my perspective:

1. The guidelines are strict and not realistic. “Normal” is now defined as less than 120/80, which, even with a well-meaning doctor and a diligent, compliant patient, will more than likely be a difficult target range to consistently maintain, especially for a middle-aged or senior-citizen patient, especially with patients who opt for lifestyle interventions alone.

2. The guidelines are meant to motivate: High blood pressure greatly increases the risk of heart disease, stroke, kidney disease, and even cognitive decline/dementia. By lowering the target ranges, patients will have to work harder on their lifestyle modification (diet and exercise) and medication compliance to keep their blood pressure lower to reduce those risks. Many of my patients don’t want to take medication, and these guidelines do state that if you are at low risk, you should give “healthy lifestyle choices” a chance first, and then I will re-evaluate you in 3-6 months. If you are at truly high risk, you need to comply with your medication to bring your blood pressure down toward these ranges.

The study authors know you won’t always hit the mark, and so do I, but the point is let’s get started!

Obesity is endemic in this country at over 33% of the population. With that comes the metabolic syndrome. And high blood pressure is part of the “deadly triad” of metabolic syndrome. The criteria for metabolic syndrome include three of the following: excess belly fat (“spare tire” or “beer belly”), elevated triglyceride level, reduced high-density lipoprotein (HDL, or “good cholesterol”) level, high blood pressure, and fasting hyperglycemia (high blood glucose levels). (NCEP Expert Panel. JAMA 2001;285: 2486).

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found an overall age-adjusted prevalence of NCEP-defined metabolic syndrome of 24% among Americans age 20 or older (Ford et al. JAMA 2002; 287:356). This is very important because this combination of factors has been shown to lead to type 2 diabetes, which is also more prevalent than ever.

For that reason, similar to the blood pressure guideline re-evaluation, endocrinologists have lowered the normal fasting blood sugar target from 114 before to under 100 now. That’s because we now know that the damage caused by too much glucose (or more precisely, by glycated hemoglobin—a.k.a. A1C—which is what we test for) to the target organs, such as the eyes, kidneys, and nerves, starts much earlier than once thought. And that damage starts with the blood vessels—which is exacerbated by…you guessed it—high blood pressure!

Further, if you already have diabetes, controlling your blood pressure is truly a life-or-death matter, according to Peter Libby, MD, Mallinckrodt Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School, and Chief, Cardiovascular Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, who stated: “The most significant threat to life in persons with diabetes is macrovascular disease…In addition to aggressive management of glucose levels, treatment to control hypertension and dyslipidemia [which literally means “bad or abnormal lipid levels,” as in your cholesterol (HDL/LDL) and triglycerides levels are out of whack] is a priority,”

3. The studies comprising the guideline may include inaccurate blood-pressure readings. Patients in the studies were asked to monitor their blood pressure at home. I am not convinced that they used proper blood-pressure measurement techniques, which could have resulted in the lack of accurate reporting on their blood-pressure measurements. In my experience I have not seen very many patients do it correctly.[1] For example, if your back is not supported, the diastolic pressure may be increased by 6 points. In addition, the systolic pressure may be increased from 2 to 8 points if your legs are crossed. Also, multiple reading throughout the day are needed since your blood pressure is constantly changing depending on mood, activity, body position, etc. What did impress me was that these guidelines devoted several pages to trying to educate doctors about properly measuring their patients’ BP.

Based on the new AHA guidelines, I developed a simple mnemonic device using the letters “BP,” to help you get an accurate reading. You can use this, whether you are having your blood pressure taken at the doctor’s office or if you are taking your blood pressure yourself at home. See below:

Also, keep in mind your blood pressure may spike as soon as you go into a doctor’s office. This is what we call “white-coat hypertension.” It has been found that people get nervous about being in a doctor’s office, and their adrenaline levels rise, causing a commensurate rise in BP. To rule out that issue, I will often recommend my patients monitor their BP at home. To rule out that issue, I will often suggest for my patients to monitor their BP at home. Buy a good-quality machine and calibrate it. Always be sure to follow my advice above on how to get an accurate reading. Keeping a log is very helpful.

4. These guidelines will result in significantly increased prescribing of blood-pressure medications. I am not convinced these lower blood pressure targets will do anything truly substantive other than increase the burden of blood pressure medications and their attendant side effects, which in turn will require other medications to manage those adverse reactions.

5. The guidelines could do more harm than good for patients over 60, if followed blindly. There are many studies that have recently shown that lowering BP to those low targets actually can harm to patients over 60 years old. One of those major trials occurred earlier this year, SPRINT (Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial), which advocates for pushing the target even lower, to under 120 mmHg, even among patients older than 75 years of age. (There is no diastolic number; the “S” in “SPRINT” stands for “Systolic,” so they did not address the diastolic component) Their conclusion was that aggressive antihypertensive drug therapy in this study population was safe and effective. However, that trial was only for high-risk patients, but notably, excluded diabetics and stroke patients. This is based merely on their “high risk factors,” such as blood cholesterol or obesity, or genetics, the data proved that even in this elderly patient population, the benefits of aggressive antihypertensive drug treatment far outweighed the risks of the drugs’ side effects—and certainly outweighed the risks of doing no drug intervention at all in this population: at this point, lifestyle interventions like diet and exercise would not be sufficient according to the SPRINT Trial.

70% of Americans over 65 have high blood pressure. Of those, nearly 50% do not have it under control.

-According to the CDC

My belief is, if I started treating most of my over-75 high-BP patients to SPRINT standards, and tried to lower all their BPs to under 120/70, that would be a very foolish—and dangerous— practice. I do not believe in a one-size-fits-all standard because I believe that each patient should be treated individually. For example, if I had a patient who had an aortic aneurysm and renal failure (because those are two “high-risk” conditions) then I would probably want their blood pressure to be closer to 120/70 even if he or she were over 60. On the other hand, if my patient were a 75-year-old female with Stage III colon cancer but with no risk factors for heart disease or stroke, then I would likely aim for a BP ≤ 150/80. In addition, I try to limit the use of blood pressure medication in older patients for several reasons:

(a) Major side effects of some of these medications may include sedation, electrolyte imbalance, and depression;

(b) Many seniors take multiple medications, increasing the potential for dangerous drug interactions;

(c) It takes longer for seniors to excrete the same dose of blood pressure medication from their body than a younger person, necessitating a dose adjustment.

**Note: If you have a loved one who is a senior citizen in an assisted living facility on any kind of blood pressure medication, always make sure to go over with the facility director all the medications your family member is taking to make sure they have taken precautions against other medications potentiating the sedative or the hypotensive (blood-pressure-lowering) effects of the BP meds. The staff at the facility sometimes add medications, such as benzodiazepines, to help patients sleep, and unknowingly create a fall risk: a common side effect with BP meds is called orthostatic hypotension. That happens when you get up too quickly from your bed or a chair, and your blood pressure suddenly drops. You can faint, and then fall that way. This is common especially in the morning, because BP drops overnight. I have many non-seniors to whom this happens as well.

In summary, I feel the reason the national guidelines recommend such strict blood pressure values is because they want to make sure the patient's blood pressure is not too far from the target. I do not think this is realistic and logical to have such low blood pressure recommendations. Based on these guidelines nearly half of Americans then become hypertensives. I am not a conspiracy theorist but most of the studies on blood pressure are sponsored by pharmaceutical companies and it is very possible that pharmaceutical companies will benefit substantially from these new guidelines.

[1] Studies relying on patients’ verbal self-reports of BP measurements can be dangerously misleading: For example, a patient's reported BP in a given study is 130/80, but might actually have been 140/85. So when the study is completed, it appears the patient’s blood pressure of 130/80 was the cause of the patient’s heart failure or stroke but in reality, their true BP of 140/85 [which was, of course, never discovered because of patient measurement error], was responsible for the poor outcome, which would have been a much more expected result for that BP.

You Might Also Enjoy...

How To Improve Heart Health at Home

What Actually Happens If You Have a Heart Attack?

Why You Should Think About Heart Attack Prevention

Learn How Nicotine Products Affect Your Cardiovascular Health